As published by the Washington Examiner by Tom Rogan

“They describe Trump’s unpredictability, his favoring of gut over hard data, his deliberate and almost reflexive ignoring of advice and counsel as simply who he is and how he operates. For some, this may provide comfort. For others, it might heighten the alarm. As with so much else about this president, he is what people want to believe about him.”

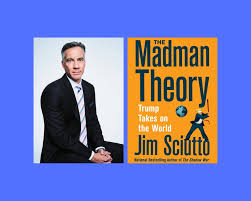

In The Madman Theory, Jim Sciutto provides a worthy follow-on to his excellent 2019 book, The Shadow War. Where The Shadow War was focused on Chinese and Russian activity in the gray space between the white of peace and black of conventional war, this outing sees Sciutto consider President Trump’s foreign policy mindset. Specifically, Trump’s apparent replicating of President Richard Nixon’s effort to convince the North Vietnamese that he was capable of doing anything, however irrational or “mad” it might appear. Although well-timed for the upcoming election, readers should not assume this to be a hit piece on the president. This is a careful examination of Trump, in which the CNN anchor and chief national security correspondent takes significant effort to give voice both to the president’s supporters and his critics.

Each chapter begins with a question that Sciutto uses as a compass for readers to chart their way through the book. This allows the reader to stay focused amid the often haywire reality that defines Trump’s policy on particular issues.

The first chapter studies some of Trump’s early decisions, questioning whether Trump’s foreign policy is “America First or Trump First?” Here, Sciutto observes that Trump’s unpredictable action is not ultimately a function of his disinterest in the details of foreign policy. Recounting Trump’s pre-inauguration phone call to the Taiwanese president, a call which infuriated China (which views Taiwan as its territory), Sciutto notes that “the call was no accident. It was the plan.”Story continues below

Each chapter examines a different strand of Trump’s foreign policy. An early and abiding focus is on what it’s like to be inside Trump’s foreign policy circle. Trump’s former guru, Steve Bannon, and his top trade adviser, Peter Navarro, feature heavily. Responding to Navarro’s defense of Trump as a much-needed antidote against the foreign policy establishment, Sciutto challenges us to step inside that worldview. “Isn’t Navarro right?” the author asks. “Who can make a convincing argument that the foreign policy establishment, to the extent that there is a contiguous group of decision-makers, has gotten the biggest foreign policy decisions entirely or even mostly right in the last several decades -whether on China, on Russia, on the Iraq War, or on a workable Middle East peace plan?”

As I say, this is not a book out to make Trump look bad. It’s a book designed to figure out how Trump gets to his policy decisions and how those decisions fit with Trump’s broader foreign policy ambitions. If there’s one sustaining theme, it’s that the president “sees himself righting an imbalance in the United States’ relationships with its allies and adversaries.”

The Madman Theory repeatedly highlights Trump’s desire to appear confident and in control. “He wants to convince Americans as much as foreigners that he’s tough,” Sciutto rightly notes, “that perceived toughness is, to him, an end itself, often in spite of damage his approach has done to alliances, or even to the state goals of Trump’s own foreign policy.”

Trump has little value for tradition or the experience of former presidents in face of foreign challenges. “Once again, this pattern is a feature, not a bug, of Trump’s approach to foreign affairs. And the president sees advantages in it, by keeping his adversaries at home and abroad off guard and relying throughout on the wisdom he trusts most: his own.”

An expert on the Asia-Pacific, Sciutto chapters on Trump’s policy toward China and North Korea are particularly strong. We see how Trump upends a failed policy of patience with China but does so with too narrow a focus on trade. We see how Trump’s rapid shift from “fire and fury” threats to personal rapport building with Kim Jong Un offers a positive stepping stone, but one that Trump fails to translate into a diplomatic accord.

Sciutto’s presentation of Trump’s Russia policy is a little unfair. The author carefully documents Trump’s odd and, by judge of American interests, unhelpful affection for Vladimir Putin. But Sciutto might have given more weight to the Trump administration’s robust policy approach toward Russia in areas of nuclear deterrence, sanctions, and operational intelligence activity. It’s debatable whether these actions to constrain Putin flow from Trump, or from those around him, but they are significant nevertheless. They deserve more consideration alongside the Obama administration’s failure to deter Putin.

When it comes to Trump and the Middle East, Sciutto makes good use of former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for the Middle East Michael “Mick” Mulroy. The former Trump official notes how the Pentagon and national security establishment waged a near-constant battle to persuade Trump that a total withdrawal from Syria would precipitate ISIS’s rebirth while empowering Russia and Iran. He correctly notes that focusing Trump’s attention on the development of oil fields in eastern Syria offered a “stealth way to avoid abandoning Syria and the Syrian Kurds entirely.” That said, it should concern us that if not for that simple oil dangle, Trump might well have now abandoned Syria to Putin and ISIS 2.0.

On Iran, Sciutto points out the incompatibility between Trump’s desire for a North Korean-style meeting of the leaders and his hawkish policy. His point, here, is that the president does not seem to recognize that acting aggressively, such as with sanctions on Iran and the strike against Iranian general Qassem Soleimani, is not necessarily a way to induce offer talks to the paranoid regime. This is a reality, perhaps, that Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has taken advantage of. While Sciutto is more sympathetic to the Iran nuclear accord than am I, he is correct in noting that Iran is now moving toward an enrichment breakout. This uncomfortable reality is one that either term-two Trump or Joe Biden will have to confront.

Ultimately, the greatest strength of The Madman Theory is that its “question” and “answer” approach serves only as a guide. The book doesn’t tell us what to think. It simply asks us to assess Trump’s rhetoric and action alongside that of his advisers and against what actually happened. A study of history, strategy, and politics, Sciutto’s conclusion is hard to rebuke. When it comes to Trump’s foreign policy, “where some see folly, others see virtue.”

The Madman Theory will be released on Aug. 18.