Is Biden stonewalling Congress? It depends whom you ask.

By Jack Detsch, as published by Foreign Policy’s Pentagon and national security reporter.

Congressional Republicans are concerned that the Biden administration is stonewalling their investigation into the chaotic U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, members of Congress and aides told Foreign Policy, after the State Department launched its own internal review of the withdrawal earlier this month.

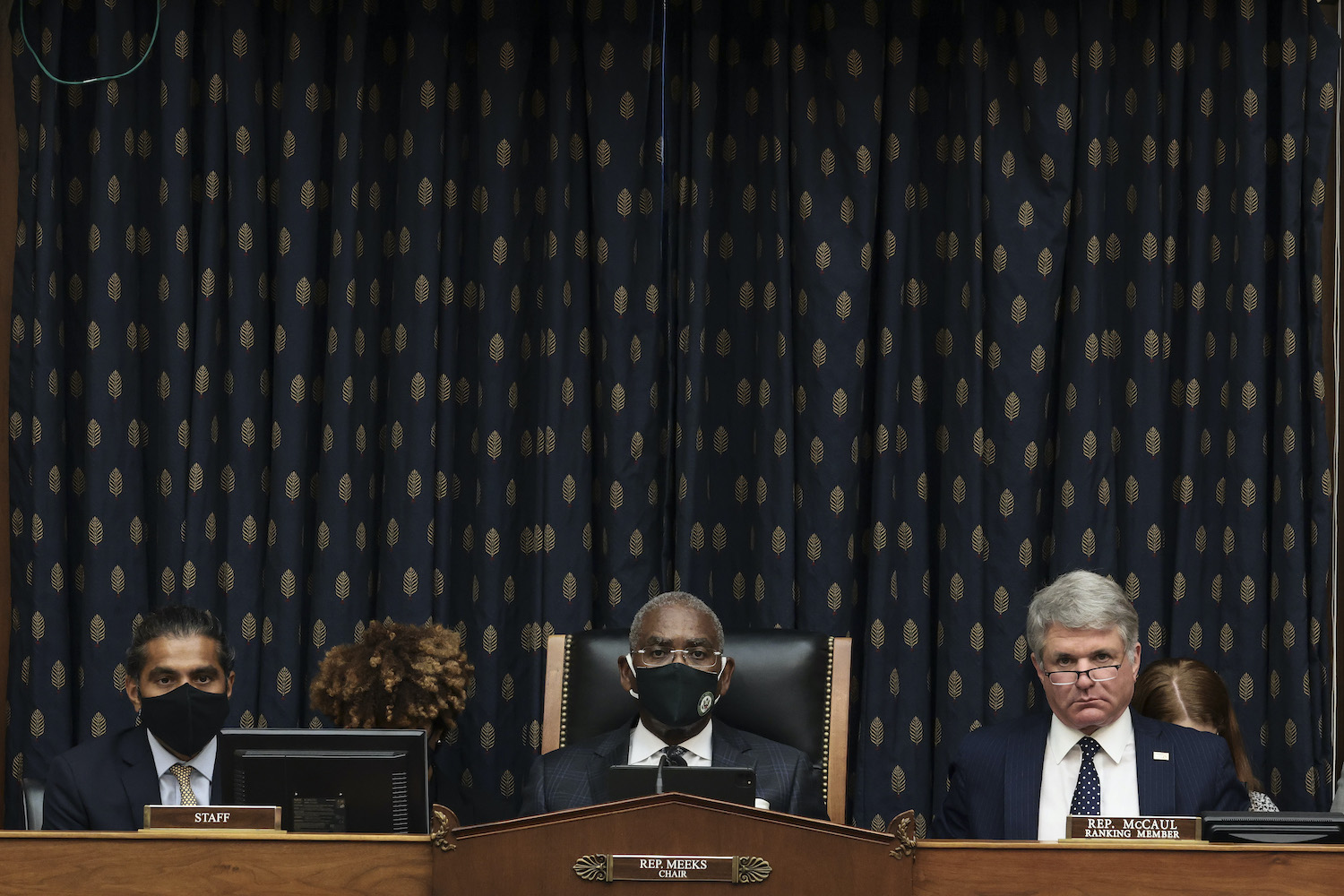

Since August, the Biden administration has not responded to seven of eight inquiries from congressional Republicans, with Secretary of State Antony Blinken responding to a lone letter from the top GOP member on the House Foreign Affairs committee, Rep. Michael McCaul, in October. The letters have requested details on the Biden administration’s evacuation plan, and called for the United States to maintain sanctions against the Taliban. Some date back to the days of the August drawdown, when the gates of the Kabul airport in Afghanistan were swamped with would-be evacuees.

The lack of answers from the administration prodded McCaul and 39 other Republicans to send an inquiry—an unusual step—asking U.S. President Joe Biden to furnish basic information about the 15-day withdrawal, including data about consultations with NATO allies, the release of violent extremists during the Taliban offensive, and the exact numbers of U.S. citizens, green card holders, and Afghans who applied for special immigrant visas still left behind.

“The administration is not doing nearly enough to investigate how the withdrawal from Afghanistan went bad so quickly,” McCaul told Foreign Policy in an emailed statement. “This mishandling is unacceptable, and the Biden administration should be working around-the-clock to find out what went wrong. Accountability here is vital and the administration should work with Congress to find out who is responsible.”

You can support Foreign Policy by becoming a subscriber.

But Democrats and Republicans on Capitol Hill appear to be at loggerheads when it comes to the scope of the investigation, as both parties eye the 2022 midterm elections. Democrats have sought to focus on U.S. government failures in Afghanistan throughout the two decades of American involvement in the country; Republicans are honing in on failures during the 15-day evacuation, the capstone to then-U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision in early 2020 to legitimize the Taliban and pull all U.S. troops out of the country.

During the end of the withdrawal, the United States helped evacuate 124,000 people but faced strong criticism after an ISIS-backed suicide blast ripped through the perimeter of Hamid Karzai International Airport on Aug. 26, killing 13 U.S. service members and scores of Afghans. And former U.S. officials insist that the Biden administration needs to explain why the evacuation was rushed and chaotic.

“President Biden seems to want to wash his hands of Afghanistan and turn away from the problem; however, with humanitarian catastrophe looming and the threat of terrorism reemerging, his administration will not have that luxury,” Lisa Curtis, a former National Security Council senior director for South and Central Asia during the Trump administration, told Foreign Policy in an email.

Republican aides fear that the State Department’s new probe could be another diversion of the agency’s handling of the Afghanistan withdrawal, and could leave out the National Security Council and the White House altogether—and all three entities made controversial decisions during the drawdown. The State Department’s internal watchdog has also launched a probe into the last days of the Biden administration’s diplomatic conduct in Afghanistan.

“President Biden must accept that Americans were disturbed by the way the withdrawal was handled and that they want explanations for why and how the administration made its decisions on withdrawal,” wrote Curtis, now a senior fellow and director of the Indo-Pacific security program at the Center for a New American Security.

But congressional Democrats fear the Republican protests show that the oversight process has already become too political, highlighted by a hearing on State Department management practices in November that turned into an impromptu grilling on Afghanistan of a top-ranking official, Brian McKeon.

It’s sparked fears of a return to a Benghazi-line marathon of inconclusive hearings that Republicans used as a cudgel against then-U.S. President Barack Obama’s second-term foreign policy after a 2012 terror attack on the U.S. consulate in Libya killed four Americans, including the U.S. ambassador to the country. That effort ended up splitting out across five standing House committees and one select committee which was specifically created in the then-Republican-controlled Congress to investigate the State Department’s response to Benghazi. The probe invited criticisms of partisanship, especially after former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was called in for marathon testimony in October 2015, in the middle of her presidential campaign.

One House Democratic aide, speaking on condition of anonymity to speak candidly about closed-door meetings, said that the State Department regularly briefed the House Foreign Affairs Committees during the Afghanistan withdrawal on the numbers of American citizens, legal permanent residents, Afghan special immigrant visa holders, and others who remained in Afghanistan. Those briefings were led by State Department Coordinator for Afghan Relocation Efforts Beth Jones and a handful of other top officials, the aide said. A State Department spokesperson declined to comment on congressional inquiries, but said that Jones and other senior officials had been routinely briefing relevant committees on Capitol Hill and individual members of Congress.

“I don’t think it’s fair to say they’re stonewalling,” the aide said, referring to the State Department’s candor toward Congress on Afghanistan. The intent of House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Rep. Gregory Meeks, the aide said, “is not going to be about doing 15 days in August,” but to understand failures across the entire 20-year war. The State Department is also being unfairly targeted for the haphazard execution of the non-combatant evacuation, the aide said, which was in the Defense Department’s lane.

A second Democratic congressional aide, speaking on condition of anonymity to describe closely-held oversight efforts, said that the Biden administration began holding cabinet-level hearings and classified briefings on Capitol Hill beginning after the August recess. It’s a far cry, the person said, from the lack of cooperation that Democrats (then in the congressional minority) got from Trump’s State Department.

“This is not the Trump era, where the American people don’t know what happened after the president got caught taking unprecedented steps to conceal his conversations with our adversaries,” the second congressional Democratic aide told Foreign Policy. “Congress is no longer forced to seek secret documents or notes from a translator as our nation’s intelligence agencies conduct a counterintelligence investigation into a sitting president. There are no foreign agents or smoking guns involved, and congressional Republicans need to realize the work to be done around the end of the Afghanistan war should not be bastardized for political posturing.”

The Pentagon’s massive $770 billion spending bill approved by Congress last week created an Afghanistan War Commission focused on flaws in U.S. policy throughout the 20-year U.S. involvement in the conflict. That is more aligned with how congressional Democrats would like to investigate the war, rather than focusing on just the two-week withdrawal.

Even beneath the partisan warfare, former U.S. officials still see major gaps in the public record of the important decisions that were made, leading to the chaos at the Kabul airport. Mick Mulroy, a former deputy assistant secretary of defense for the Middle East and ABC News analyst, said that the Biden administration needed to provide answers on why the United States closed Bagram Air Base before the evacuation began, and if the number of U.S. forces was capped during the process.

Curtis, the former National Security Council official, wrote that the Afghanistan War Commission should examine why the Trump administration forced then-Afghan President Ashraf Ghani to release 5,000 Taliban prisoners; she also called out the Biden administration for failing to foresee the collapse of Ghani’s government in August.

“Unfortunately, the effort to explore what went wrong in Afghanistan has already become partisan,” Curtis wrote. “This was a national failure and Republican and Democratic administrations alike made mistakes in Afghanistan. If Republican leaders insist on trying to use Afghanistan only to bash Biden, all Americans will lose because our nation will fail to learn from its mistakes and make similar foreign policy blunders in the future.”